School Programs – Field Trips

SCHOOL FIELD TRIPS

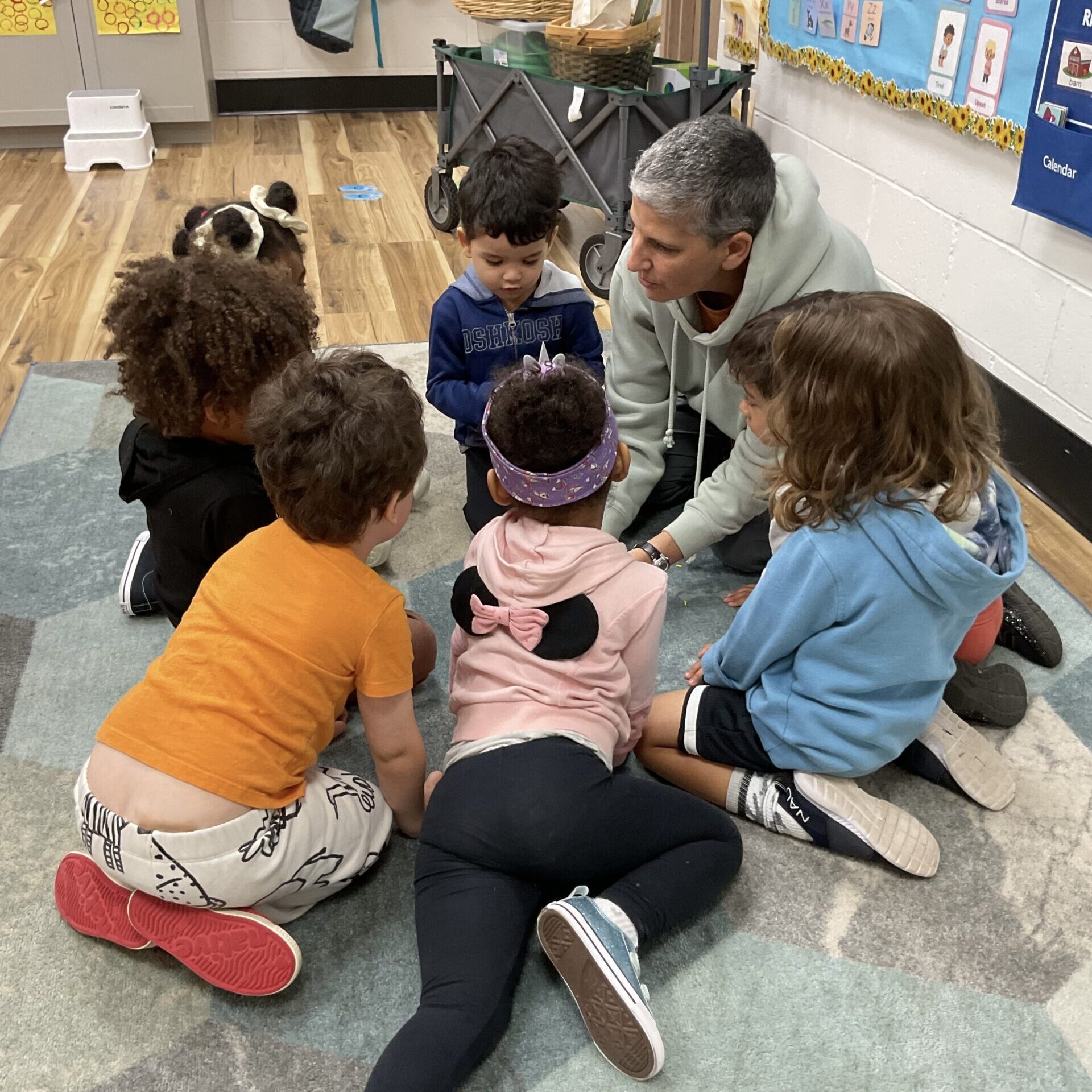

Each year our talented staff members and volunteers have the joy of working with more than 5,000 children from area schools. Our hands-on and active programs keep students involved from beginning to end.

Our property is 102 acres and has gently rolling pastures, coniferous and deciduous woodlands, a marsh, a pond, and streams. We have such diverse resources as 19th-century barns, a maple syrup shed, several telescopes, an astronomy classroom, and an authentically recreated encampment with a barked wigwam and a thatched longhouse. Our pastures and barns are home to a very engaging bevy of beasts- cows, sheep, a flock of chickens and proud roosters, and two pigs in the warmer summer months. Our best resource, however, is our enthusiastic and experienced staff; they pay special attention to details that make our programs unique and very keyed into children’s learning abilities.

All programs are 90 minutes in length.

Book Your Field Trip Today!

Fall FARM & FIBER

HABITAT HUNT

Maple sUGARING

ADAPTATIONS

On farms across the land, fall and winter were wonderful times to turn sheep’s fleece into yarn for knitting and weaving. Our flock of Romney sheep will be featured guests in this program. Your students will meet our sheep and lambs, feel their insulating fleece, and then take previously shorn fleece through the steps required to make it usable fiber. They will wash the fleece, hand-card (comb) it, and hand-spin it into yarn with a partner.

Eastern Woodland indians

This popular program provides a look into an important Native American culture that inhabited the eastern woodlands for centuries. Classes will hike to our encampment, comprised of a thatched longhouse, barked wigwam, and activity areas. They will learn about the daily activities of the Connecticut Indians, including the important roles played by all family members, home life, cooking, and the use of ceramics. We will point out plants that were gathered for food, medicine, and even tools. We will also try our best to “stalk” quietly, like skilled Indian hunters. We will also discuss how women crafted clothing from animal skins, and the importance of the seeds, nuts, and berries gathered by children through spring, summer, and fall.

.This exciting hands-on program gives students a chance to explore and compare woodland, pasture, and stream habitats. Young explorers will learn how each habitat functions as a community, and how plants and animals rely on each other for survival.They will learn about food chains and natural recycling. In the woodlands, we’ll overturn rotting logs and discover the community of insects, arachnids and other arthropods that make their homes there.

FRESHWATER EXPLORATION

We are fortunate to have a stream, pond, and marsh on our beautiful property. Each of these habitats is unique, and teams with aquatic plants and animals.

Using fine-net strainers, students will catch a variety of life forms, ranging from dragonfly and damselfly nymphs, water boatmen, larval salamanders and tadpoles in the marsh, to crayfish, hellgrammites, water pennies, and minnows in the stream.

As our buckets begin to fill with an assortment of creeping, crawling, and swimming creatures, students will learn about the adaptations and survival strategies that enable the plants and animals to live in their respective habitats.

Our maple syruping program is an ideal way to counter late-winter blues. Students will be a part of the reawakening of the woodlands as the sap begins to rise in the sugar maples. By participating in the tapping, collecting, and boiling down of the maple sap in our evaporator, they will learn valuable lessons in tree identification and the life cycles of deciduous trees.

SPRING FARM & HONEY BEES

One of our most popular offerings is our spring farm program. In this fast-paced world, it is increasingly important for children to understand the importance of food production and how it is tied to farms. Far too often, when we ask our students where food comes from, they reply, “The grocery store!”

Our honeybees are a wonderful part of the program. Through photos, props, and an indoor observation hive, the children will learn the vital role these insects play on the farm in pollinating our trees, shrubs, flowers and, of course, making delicious honey.

Everyone will taste honey made by our own bees and make a beeswax candle to bring home.

A close up look at claws, talons, beaks, eyes, ears, noses, and more! Live and mounted specimens will help students to understand why animals look and behave the way they do.

This interactive new program provides an excellent opportunity to enhance the Adaptations science units found in grade 1 and in grade 3. Utilizing a scaffolding pattern along grade levels, our engaging staff members offer an exciting range of appropriate activities to both grade levels.

EROSION